The failed coup attempt has resulted in a widespread and thorough crackdown in Turkey, providing President Erdogan with an unprecedented opportunity to centralize power. Less publicized however are the similar crackdown attempts against the Gulen movement throughout Eurasia, which has left few in the Caucasus and Central Asia unaffected.

Background

Following a failed coup attempt this past July, the Turkish government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan has begun a thorough campaign to cleanse his state and security services of the Fethullah Gulen network, believing that the Pennsylvania-based religious leader was the mastermind of the coup attempt. Much has been written on this subject in the month that has followed, with excellent material now available at the Washington Institute, War on the Rocks, Foreign Policy Magazine, the BBC, the Council on Foreign Relations, and other sources. This article will not try to cover the same ground, but rather focus on the consequences of the Turkish crackdown across Eurasia.

The Movement in Azerbaijan

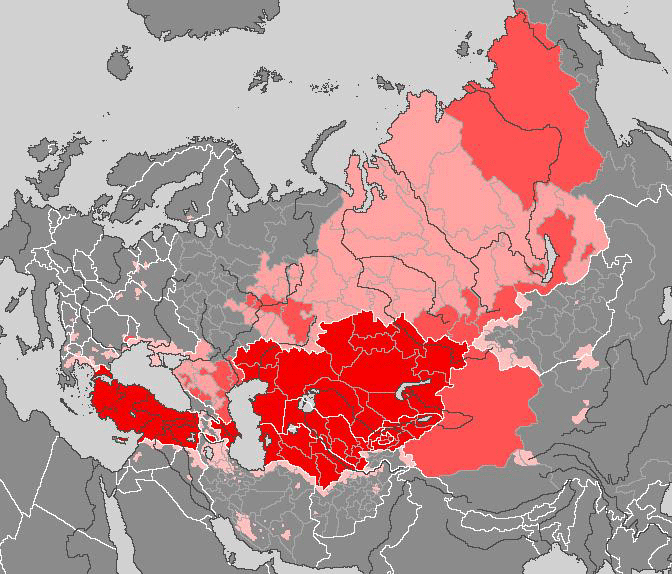

Representatives of Gulen, colloquially known as Hizmet meaning “service” have been active in the post-Soviet republic ever since the disintegration of the USSR in 1991. Their goal was to seed a revival of Islamic life in the country, which had been thoroughly secularized during Soviet rule. Gulen’s network focused on influencing Azerbaijan’s education system, business world, and media establishment, going so far as to set up the first color printing press in Azerbaijan. The group published a professional magazine called Zaman and operated a Turkish-language TV station called Samanyolu (the Turkish and Azerbaijani languages are mostly mutually intelligible) in an attempt to reach as large an audience as possible. Though not explicitly stated, the Gulen movement is overwhelmingly oriented toward the Turkic-speaking world, consisting of Turkey, Azerbaijan, most of Central Asia, as well as the Crimean and Volga Tatars of Ukraine and Russia.

Though the Gulen movement had largely fallen out of favor with Azerbaijani authorities in the mid-1990s, little direct action has been taken against them until the past few years. Azerbaijani society is overwhelmingly secular, but with a Shi’ite heritage. Thus it has proven difficult for Sunni extremists to establish a foothold there, despite their successes in Chechnya, Dagestan, and elsewhere in the Caucasus. The Islamic hardliners Azerbaijan does have tend to be of the Shia variety, and operate under consistent government pressure including frequent prosecution and being monitored for fear of acting as Iranian agents.

Thus, it made instant headlines when Baku began to clamp down on Gulen sympathizers. This past March, the Azerbaijani government seized control of 11 Turkish-language high schools, 13 university-exam preparation centers and the prestigious Qafqaz University, handing over administration to the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijani Republic (SOCAR). All of these institutions were previously operated by a Turkish education company known as Çağ Öğrətim, “Era Education,” with suspected Gulenist ties. More recently, Baku has closed an Azeri-language newspaper affiliated with Gulen. Though Azerbaijan has not yet declared the entire movement to be a terrorist organization, the pressure is clearly on.

And it is not limited to Azerbaijan.

Severed Ties in Tajikistan

Early this month, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon shut down all Gulen-linked schools in his country by Presidential decree. Tajikistan’s Hovar news agency reported that seven “Tajik – Turkish high schools” which were previously associated with Şelale Educational Institutions were transferred to the control of the Tajik government. Gulen schools in Tajikistan, called dershanes, specifically targeted students from the country’s poor and underfunded public schools in an attempt to gain influence from the ground up.

Many express fears that Gulen and his allies are thus contributing to a growing Jihadist threat throughout Tajikistan, though evidence of such links has hardly been conclusive. Tajikistan has seen a significant increase in Jihadist activity in recent years, most notably when the American-trained head of Tajikistan’s security force, Gumurod Khalimov, defected to the Islamic State (see a Leksika briefing on this subject here). Given the country’s proximity to Afghanistan and increasingly unstable domestic situation, Dushanbe certainly has good reason for concern.

Kyrgyzstan

This increasing scrutiny of Turkish schools across Central Asia has also spread to Kyrgyzstan in a very public fashion. A conflict between two universities in the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek has grabbed local headlines in recent weeks. On one side is the Turkish state-funded Manas University, and on the other is the Ataturk-Alatoo University funded by Gulen.

As reported by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “Immediately after the coup was crushed, the Kyrgyz rector of the Ankara-funded Manas University organized a forum to denounce the attempted putsch. Sebahattin Balf also used the forum on July 18 to publicly warn his fellow citizens that the Gulen group could equally make “people in Kyrgyzstan do terrible things in their own country.” This not-so-subtle allegation that Gulen sympathizers could be engaged in treason helps to highlight domestic divisions within Kyrgyzstan.

What’s Next?

Gulenists, both real and suspected, continue to be purged in Turkey. Thousands remain in detention from the armed forces alone. The Turkish government is demanding Gulen’s extradition from the United States, though no official agreements have yet been reached. President Erdogan is seizing unprecedented power, centralizing the entire Turkish state around himself. Turkey’s political future remains in the balance, with many in the West questioning Ankara’s membership in NATO and even bilateral cooperation agreements. The future status of American nuclear weapons in Turkey has also been called into question by top analysts and regional experts.

Turkish strategists seem cognizant of these concerns, taking recent steps to normalize relations with Russia and doubling-down on their support for the opposition in Syria. Ankara is likely trying to expand their strategic options in a region which continues to implode. Turkish forces are now directly intervening on the ground in Syria. In the recently-launched Operation Euphrates Shield, Turkish forces fought alongside various opposition groups against Kurdish and IS positions in a three-way conflict along the Turkish border north of Aleppo.

Given domestic instability, it is likely that Turkey will continue to assert itself in foreign policy as a means of creating national unity. What this means for the region remains to be seen, however the Turkish entry into Syria has already changed the dynamic of that war, with the potential to effect realities on the ground in Iraq as well. Turkey and Russia continue to maintain a difficult balance, each having very different visions for the future of Syria as well as supporting opposite sides of the Karabakh conflict. Turkish relations with Iran have long been strained, with little hope for improvement for the foreseeable future. With growing alienation from the West, few friends in their neighborhood, and continued instability at home, Turkey will be a place to watch for a long time to come.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons